Trauma-Informed Practice: Safety Isn’t a Bonus. It’s the Bare Minimum.

A Guide for Parents Who Are Done With Sticker Charts!

Let’s say your child has just flipped every chair in the classroom. Again.

They’re in tears. You’re in the principal’s office. The school’s calling it “non-compliance.” You’re calling it Tuesday. The school are rambling on about attendance issues, defiance and asking if a new rewards chart is the answer.

Your sisters words float in the back of your head ‘you’re being too soft on him’…

And in your email inbox, the NDIS is reminding you that your funding for behaviour support is half gone — and surely, six months is enough to ‘fix’ this... right?

Or maybe it’s not a classroom. Maybe it’s at OT where your kiddo has shut down completely — curled under a table, not speaking, not moving, refusing eye contact. The therapist, bless their cotton socks, keeps smiling and nudging them toward the sensory obstacle course that no one asked for. You sit there, half-apologising, half-wondering how this counts as therapy. Then comes the follow-up email: “Didn’t engage today — let’s try again next week.”

And don’t forget the glaring eyes of judgement that our kids feel at the times they’re not able to ‘perform’ as expected.

The autonomic meltdown in Target that looks like a tantrum over the latest Nintendo Switch. Being asked to leave the trampoline park because they “weren’t following the rules” — even though the rules were shouted through a loudspeaker and delivered in rapid-fire instructions that would confuse anyone, let alone a sensory-sensitive seven-year-old. The dirty look in the waiting room when your kid doesn’t say hello to the receptionist. The impatient and over-scheduled doctor telling your teen to stop being ‘overdramatic’ when they need their eyes checked - despite the fact that the examination literally involves having piercingly bright lights flashed into their sensitive retinas.

And it’s in those moments — under desks, in Target aisles, in the backseat of your car after another therapy session that felt more like a test — that you start asking: Are we actually helping or are we harming?

What Is Trauma-Informed Practice?

Firstly, let’s separate ‘trauma’ from ‘trauma informed practice’ because they are not the same thing. And don’t forget - we can’t talk about ‘TRAUMA’ in front of the NDIS. They automatically freak out thinking they’re funding mental health support *gods forbid*.

Trauma is what happens to a person and how they respond. It might be a single event, or a slow burn of stress and unmet need that rewires how someone experiences safety, trust, and connection. For kids, trauma isn’t just the “big” stuff — it can be medical trauma, sensory overload, systems that punish difference, or living in a world that constantly misunderstands them.

Trauma-informed practice, on the other hand, is providing support to a person while taking into account their life experiences and how those experiences have impacted and continue to impact them.

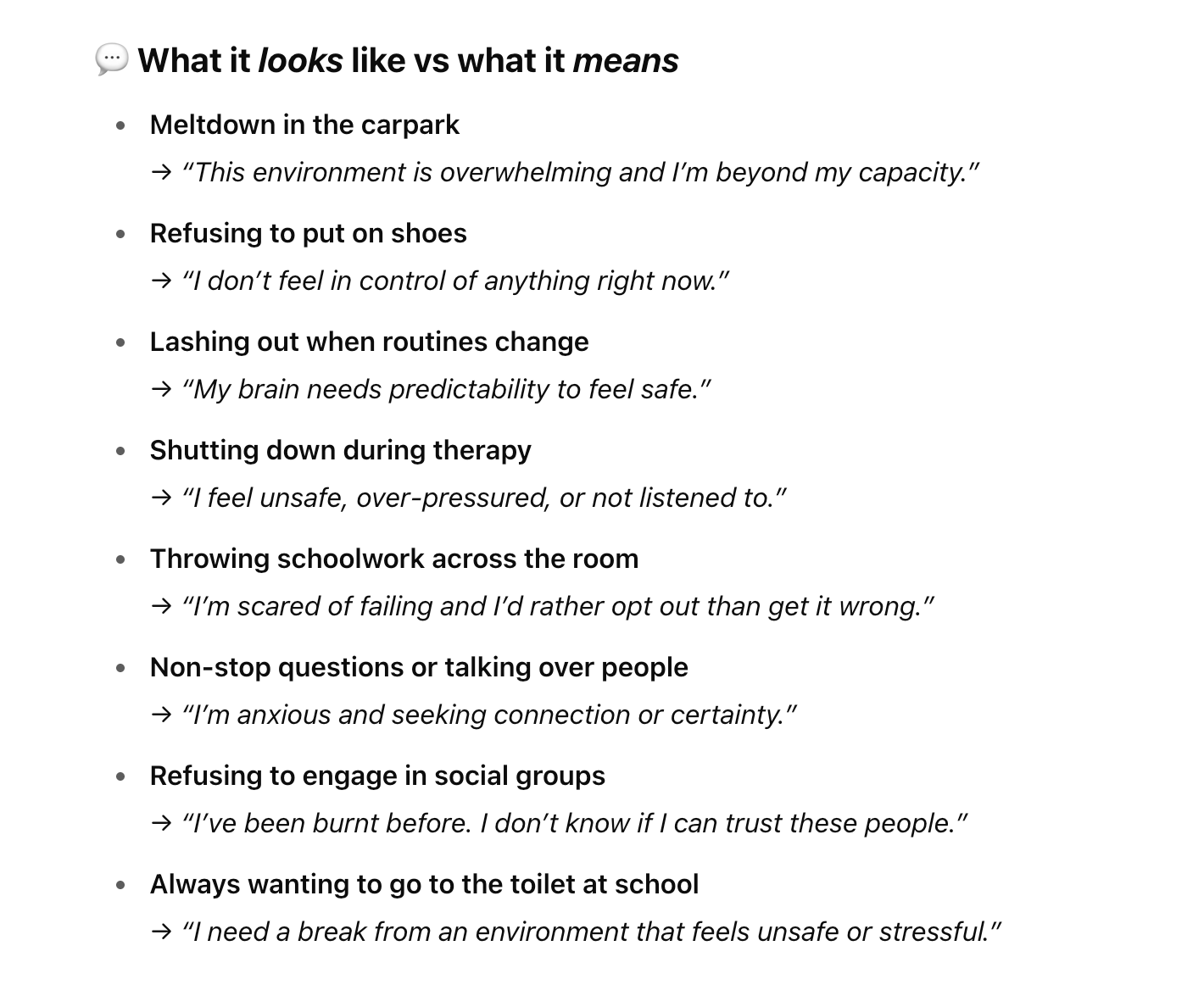

Its the difference between asking, “Why is this child melting down over a pencil?” and wondering, “What has this child been through that makes this pencil feel like the last straw?”

It’s seeing a slammed door and asking, “What does this child need right now?” instead of “How do I stop or punish that behaviour?”

Or noticing a child hiding under a table and asking, “What’s feeling unsafe for them right now?” instead of, “How do I get them to rejoin the group?”

Its the process of pausing to recognise trauma’s impact and respond with care, not control.

“Trauma-informed care shifts the focus from ‘What’s wrong with you?’ to ‘What happened to you?’”

— Sandra Bloom

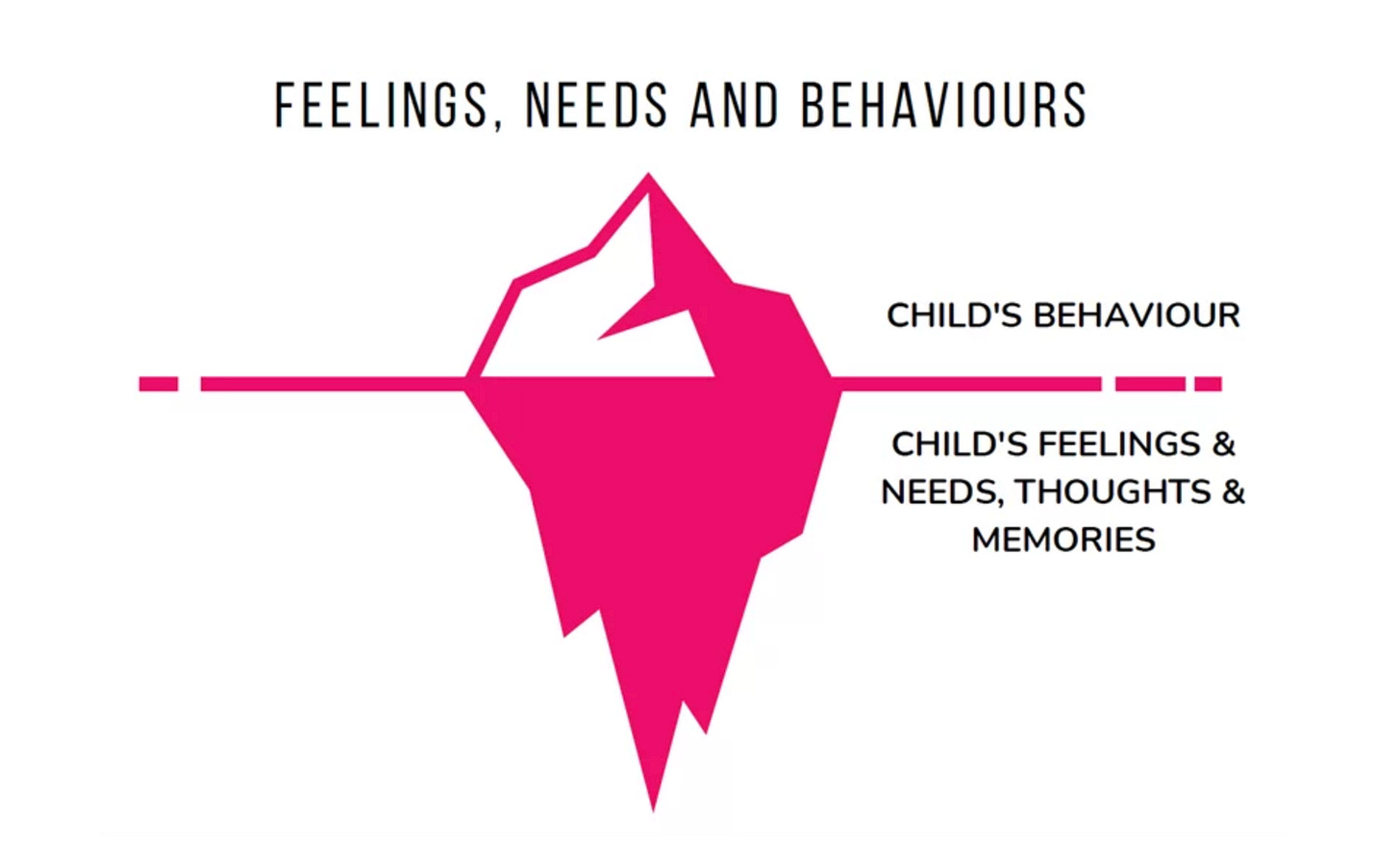

Instead of looking to eliminate or control behaviours, we lift up the hood and get super curious and non judgemental to ask ‘what is this child trying to tell me through their behaviour’?

Behaviour is Communication.

Always. In all ways.

Every eye roll.

Every shutdown.

Every time they ‘refuse’ to put on their shoes or won’t (can’t) get in the shower — it’s not just “bad behaviour.” It’s a message.

Sometimes it says, “This is too much.” Other times it’s “I don’t feel safe,” or “I need help but don’t have the words.”

We’ve heard this before right? Our kids aren’t giving us a hard time — they’re having a hard time. But that concept can be hard to keep front and centre when rushing out the door to Physio, you’re 20 minutes late, someone’s crying (maybe it’s you), and the shoes are still in orbit somewhere near the kitchen.

In the classroom with 27 other kids and no lunch break because the teacher has yard duty, are they really in a position to ask, “What is this kiddo trying to tell me?” instead of “How do I make it stop?”

So now we’ve really arrived at the crux of the issue…

How many of us adults are truly, genuinely well regulated throughout the day ourselves, so that we can even start to take a trauma informed approach to those around us or even attempt to co-regulate for and with them?

Don’t answer that. No one wants to go there right now. Adulting is hard and that’s a topic for another article.

But let’s look at distress signals dressed up as bad manners:

What the world fails to remember time and time again is that trauma doesn’t always look like a Big Bad Event™. Sometimes, it’s death by a thousand tiny misunderstandings. It’s being forced over and over again into environments that feel unsafe or over demanding. Being asked to perform emotional labour for the comfort of adults. Being taught that your body, your voice, your reactions are “wrong” unless they fit a neurotypical template.

And frequently our kids just don’t have the emotional intelligence or self awareness to ‘use their words’ and say ‘‘The hum of the fluorescent lights is making my skin crawl,’ or ‘I’m panicking because I don’t understand the classroom instructions and everyone else is already halfway through the task.’ And let’s be honest — most of us adults aren’t exactly models of emotional regulation either. We just rage-text a bestie and then eat five slices of left over birthday cake.

The coping mechanisms (healthy or not) that we develop as adults are often not available to kids who have such little control over their own lives. This isn’t Basgiath. We're not training soldiers — we’re supporting humans.

So when the systems built to support our kids — school, therapy, even the NDIS — are more focused on outcomes than understanding it’s no wonder we are left shaking our heads asking: Where is the humanity in all of this?

So what should Trauma-Informed Practice Look Like?

A trauma-informed approach asks, “What happened to you?” instead of “What’s wrong with you?”

When we first allow someone into our child’s world, we are inviting someone into the messy, beautiful, exhausting, sacred chaos of our lives. That person is about to witness meltdowns, victories, regressions, breakthroughs, and moments where the wheels completely fall off. They’re going to see our kiddo at their most vulnerable and they’re probably going to ask a lot of that child too!

Think about the trust that involves! And trust isn’t built with sticker charts, compliance and KPI’s. It’s built when your child knows they can say no, fall apart, shut down, and still be treated with respect and curiosity.

Trauma-informed practice means showing up human first, professional second. It means:

Building trust over time, not forcing connection

Respecting consent, even when it's messy

Listening to behaviour like it’s a language (because it is)

Ditching the “fix-it” energy, and focusing on relationship

Being flexible, not formulaic

Imagine you finally matched with someone decent on Tinder. After a week of witty banter you agree to a first date.

You walk into the café, sit down, and before you've even opened the menu, they say:

"Just an FYI - for this to work I need to know that you’ll always stay calm, smile even when you’re upset, and never raise your voice or set a boundary."

…Excuse me?

Did I just swipe right on a walking red flag?

That’s what it can feel like for a child when someone expects constant compliance, emotional regulation, and “good behaviour” — with zero rapport, no trust, and absolutely no consideration of the child’s lived experience.

Now imagine that same date says,

“If you make it through this date without arguing, I’ll get the bill.”

It’s giving… transactional.

Immediately no.

Conventional behaviourist approaches are basically the patriarchy in a polo shirt — all about control, compliance, and making you earn your sticker. It expects kids (and often parents) to stay agreeable, compliant, regulated, grateful, and low-maintenance at all times — regardless of their needs, context, or past experiences.

But our kids don’t need dominance disguised as help!

Why does a Trauma Informed lens have such an impact?

Many disabled children experience trauma — from medical experiences, system failures, exclusion, or daily ableism.

Kids can arrive into a therapy or school setting already carrying layers of trauma — and need support, not suspicion.

The emotional toll of needing to tell your story to seven different services plus "prove" disability and support needs over and over again

The intersection of disability and trauma: diagnostic journeys, medical trauma, exclusion, restraint, and behaviour regulation

Repeated invalidation and powerlessness creates a re-traumatisation loop

Children with disability constantly live with experiences of being misunderstood or labelled “difficult” instead of supported

And of course:

The Intersection of Disability and Trauma

Disability is not inherently traumatic — but how society responds to disability often is.

Examples of trauma intersections:

Medical trauma (frequent procedures, early hospitalisation)

Sensory trauma (overwhelm in constantly inaccessible environments)

School-based trauma (seclusion, exclusion, restraint)

Systemic trauma (NDIS reassessments, funding inadequacies, loss of services, parent blaming)

Our kids Are Not KPIs

One of the most important things we can remind ourselves — especially when we’re knee-deep in NDIS reports, funding requests and provider emails — is this: our kids are not here to prove that therapy is working.

PS - if the therapy isn’t helping then umm hello… why are we blaming the child?

When therapy is driven by rigid outcomes and “End of Plan Progress Reports,” it stops being about the child and starts being about the funding.

Too often, therapists and services are pressured to demonstrate improvement on paper — whether it’s increased participation, reduced behaviours / RP’s, or ticking off arbitrary goals.

Your child is not a productivity measure. Not a behaviour chart. Not a KPI on someone else’s whiteboard. And progress doesn’t always look like a line that moves up and to the right — sometimes it’s circular, sometimes it’s sideways, and sometimes it just stops completely for a while. That’s okay.

Maybe your kiddo doesn’t “achieve” something in every session. It’s okay if you can’t point to a neat dot-point in a progress report. It’s okay if they just need to sit under a table and breathe. That doesn’t mean you’re wasting time or money but it might be a time for reflection that if your child is overwhelmed, shutdown, or stuck in fight or flight, it's okay to switch things up or slow things down.

You don’t have to “use all your funding” if what your child needs most is rest. Therapy is most helpful when a child feels safe and regulated — and if that’s not the case right now, taking a break might be the most healing choice of all.

Growth can’t happen from a place of bare-bones just scraping through survival and our kids can’t push themselves to develop new skills while they are still stuck in fight, flight, freeze, or fawn.

Their brains aren’t wired for learning when they’re busy trying to feel safe. First we regulate, then we connect — then we can even think about skill-building.

They are complex, feeling humans with histories, sensory profiles, communication differences, and often trauma that can’t be plotted neatly on a spreadsheet.

A child’s “challenging behaviour” might actually be a survival response, a communication strategy, or a sign that something in the environment isn’t working for them. When we focus only on functional outcomes, we risk missing the why entirely — and worse, we risk retraumatising kids in the name of “support.”

Permissive parenting vs Trauma Informed Approach.

Here comes my Ted Talk: being trauma-informed is not the same as being permissive.

You can hold boundaries and be calm and compassionate. You can say “no” and still be safe, regulated and kind. A trauma-informed response doesn’t mean letting your child run the show or avoiding every hard moment — it means understanding why that moment is hard, and supporting them through it without shame, punishment or power plays.

Permissive parenting says, “Do whatever you want, I give up.”

Trauma-informed parenting says, “I see that you’re struggling, and I’m going to help you feel safe while I hold this limit.”

It’s not about removing all expectations. It’s about matching them to your child’s nervous system and capacity — and knowing when to step in with co-regulation instead of control. When our kids need safety and structure it can’t come from dominance or being told ‘what you’re feeing isn’t real or valid’.

It’s hard when the world around you expects compliance, politeness, and “good behaviour” all. the. time. — no matter what is simmering below the surface.

Where Does Positive Behaviour Support Fit In?

Having the word ‘Behaviour’ in the title is an issue for many.

And I get it - this harks back to ABA and compliance based intervention.

My opinion on ABA and all therapies are that they are only as effective and respectful as the person’s implementing them and the theories underpinning that service delivery.

So in my opinion, Positive Behaviour Support (PBS) can be a game changer — but only if it’s grounded in trauma-informed practice.

The danger is when PBS plans become a glorified instruction manual for “fixing” behaviour, instead of understanding what’s underneath it. That’s when you start seeing red flags like token boards, planned ignoring, or cookie-cutter strategies that treat your child like a set of checkboxes.

The other issue is that the NDIA keep harking on about capacity building (yesterday please!) and progress reports, as if its realistic to see dramatic change occur within a matter of weeks - even if the funding isn’t there for a wrap around holistic family centered approach. We can’t just fund PBS without also looking at other therapies, communication methods, carer support and training, up skilling school and kinder, the support worker team, grandparents and other informal supports.

Imagining that 12 months of PBS in isolation will *poof* resolve all the issues is just as realistic as expecting a scented candle to heal intergenerational trauma. Its giving Dollar Store disability support and we can’t underfund the village and then act shocked when the roof caves in.

At its best, PBS should centre communication, nurture co-regulation, and genuinely collaborate with the child and family. Like a powerful tool for understanding the function of behaviour — not punishing it out of existence.

Because behaviour isn’t the problem. It’s the cry for help.

Government Paternalism & the Trauma of Gatekeeping

The NDIS was meant to offer choice and control — not constant auditions that feel like a high-stakes custody battle.

Proving your child’s needs over and over again is usually not a strength based approach. We have to focus on deficits and impairments and holes in the walls. It’s not empowerment and it plays out in a system with a staggering power imbalance.

We engage with paternalistic bureaucracy dressed up as “safeguarding” while attending plan reassessments that feel like cross-examinations asking why 24 hours of OT support wasn’t enough to single-handedly ‘fix’ complex behaviour rooted in years of exclusion, misdiagnosis, or unprocessed trauma.

It’s a system that says “we know best” — and by “we,” they mean a faceless agency that seems to have no accountability or long term understanding of "primum non nocere” or ‘First Do No Harm’.

How to Advocate for Trauma-Informed Support

You shouldn’t need a PhD to ensure your kid gets support that’s safe, respectful, and actually helpful — but here we are. So if you ever feel pressure to “get outcomes” at the expense of your child’s comfort or emotional wellbeing, take a breath. You are allowed to push back. You are allowed to say, “I want therapy that centres connection, not compliance.

If you’re a parent trying to figure out whether a provider gets it (like really gets it), start with questions like:

“How do you adapt your approach for children who struggle with emotional regulation?”

“What do you do when a child is dysregulated or shuts down?”

“How do you include families and caregivers in goal-setting and planning?”

“What kinds of threat responses or adaptations do you think are being used by my child? What coping mechanisms are they using to protect themselves?”

Imagine if instead of seeing challenging behaviours as the problem a therapist asked our child:

What do you have to do to cope with daily life?

How much power or autonomy do you feel you have in your day to day life?

Do you feel like people are listening to you?

Do you feel heard?

Do you feel understood?

Do you have an idea of how your child would answer these questions already?

When a session isn’t going well, don’t feel like you have to bite your tongue or invent a fake emergency at home to get out of there early. You can speak up to guide the process into a more trauma informed approach. This might sound like:

“Right now, I think connection is more important than participation. Let’s just be with them in this moment.”

“When he’s like this, he’s showing us that he doesn’t feel safe. Can we pause the task and focus on helping him feel safe with us again first?”

“Before we talk consequences, can we try to figure out what triggered this? That’ll help us prevent it next time.”

“She’s doing the best she can with what she has right now. Let’s assume there’s a reason behind the behaviour.”

Today might be a trust-building day, not a goal-crushing one.”

“Can we talk about this in a way that assumes he’s struggling, not misbehaving? That shift really matters for us.”

Initial onboarding meetings with new services are the place to say it out loud: “We’ve seen what happens when support is not trauma informed. We don’t want to repeat that.”

Say it kindly, say it clearly — but say it.

In Conclusion: Safety is the Minimum. Trust is Everything.

Trauma-informed care shouldn’t be some gold-star, bonus-level, once-in-a-blue-moon type of support. It should be the starting point. The bare minimum before capacity building begins.

If a provider or system can’t offer trauma-informed support, then it’s not a safe support. Period. It’s not too much to expect better. It’s not being “a tricky parent” to ask how a provider responds to dysregulation, or whether they build trust before pushing outcomes.

Telling your families story over and over again can be emotionally exhausting and can actively contribute to re-traumatisation. Trauma-informed systems recognise this and build in ways to listen once, listen well, and avoid rehashing the pain just to access help.

This is why trauma-informed practice is a fundamental reframe — away from “fixing behaviour” and toward understanding experience. It’s pausing to ask not “What’s wrong with you?” but “What happened to you?” and taking that next step to “What do you need right now to feel safe?”

And if that question isn’t at the centre of every plan, every strategy, every supposedly “person-centred” support, then we’re not doing the work. We’re just rearranging the desk chairs while the classroom explodes. Again.

Till next time,

x Anna

🔎 Looking for Further Reading, Resources & Policy?

If you’re keen to dig deeper (or need to come armed to your next planning meeting), here’s where to start:

NDIS Practice Standards – Especially the sections on participant safeguarding, person-centred supports, and dignity of risk.

Behaviour Support Rules 2018 – The actual rules behind what providers can and can’t do when it comes to restrictive practices.

Disability Royal Commission – Final Report – Particularly the volumes on inclusive education, restrictive practices, and children with disability.

UN Convention on the Rights of the Child – Articles 23 (children with disability), 24 (health), and 39 (recovery from trauma) are especially relevant.

And for practical tools and family support:

Ask Izzy – A national directory to find local support services by postcode.

ACD – Association for Children with Disability (Victoria) – Resources, advocacy, and peer support for families in Victoria.

CYDA – Children and Young People with Disability Australia – National voice for children and young people with disability and their families.

The Healing Foundation – Supports intergenerational healing, with strong resources for First Nations families and community-led approaches to trauma.

These resources won’t fix the system overnight — but they’ll help you speak the language, back up your requests, and hold services accountable.